Men's Health Magazine - What Happens When the Army Needs 36,000 Kettlebells, Fast

This is the remarkable true story of the largest order of fitness equipment ever placed.

THE MILITARY brass all traveled to the South. Twelve higher-ups from different groups within the Army, like TACOM (Tank Automotive and Armaments Command) and DCMA (Defense Contract Management Agency), who had all sorts of titles and ribbons and badges and awards among them. They exited I-20 in Lexington, South Carolina, and passed a Waffle House, Circle K, Bojangles, and Dairy Queen. A final turn led them down a rough road that ended at a palmetto--flanked entrance. The rectangular warehouse was more than two football fields long and walled in sheet metal. Five-foot-tall block letters—SORINEX—crowned the entrance.

Out front were pickups of all kinds. Lifted, burly--tired, black and tan and white and red Fords and Chevys and Rams. Picture the parking lot of Bass Pro Shops. The Army’s top minds were here to inquire about whether the southern gearheads in this place could help them solve a national-security problem that was hitting critical mass.

This was early 2019, and although we had the most technologically advanced fighting force ever—able to conduct Hellfire-missile strikes from Predator drones piloted by men thousands of miles away—new research had found that soldier fitness had declined over the past few decades. Roughly 12 percent of active-duty soldiers were obese, a figure that had risen 61 percent since 2002. Obesity-related health care and recruiting cost the government $1.5 billion annually.

The Army was planning a generational shift in its culture of fitness that was going to start with its fitness test. Since 1980, the test had been simple—pushups, situps, and a two-mile run. But the new realities of war, military researchers determined, required a test that included forward-thinking strength and conditioning exercises: trap-bar deadlifts, medicine-ball throws, kettlebell farmer’s carries, sled sprints, and that two-mile run. Which meant the Army needed new fitness gear.

Lots of it, including:

1,098,240 pounds of hex barbells.

10,067,200 pounds of bumper plates.

183,040 pounds of medicine balls.

1,464,320 pounds of kettlebells.

That’s 12,812,800 pounds of stuff that is heavy for the sake of being heavy, equal in weight to 2,135 of the pickups parked out front. And by government mandate, it all had to be made in America. In six months.

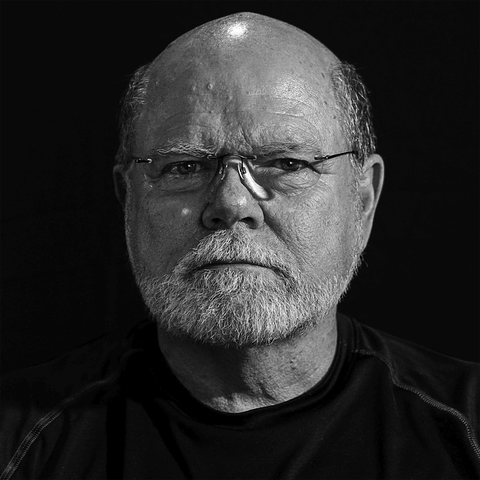

The contract was available to any American company that thought it could fill it. The brass had already heard plenty of pitches, but they were here for another. Bert Sorin and Nelson Lewis, a sort of Mutt and Jeff of the exercise world, stood at the front of a conference room. Sorin is Sorinex’s 40-something, big-idea, outfacing CEO; Lewis is its late-60s, number--driven, behind-the-scenes COO. Sorin is a former All--American D-I track-and-field thrower, six-foot-three and a muscular 230 pounds, with a curly beard that drops to mid-chest. Lewis is “not an exercise dude” and balding. Sorin’s a backcountry big-game hunter, Lewis a bass fisherman. Sorin the Yes Guy, Lewis the No Guy.

The No Guy led off and did what No Guys do. “Well, first off,” he said, “this is an almost impossible thing that you’re asking. There’s just not enough raw materials to do this. There’s not enough of the right steel available to fulfill this order. There’s not enough crumb rubber for the bumper plates. There’s not enough . . . .” And on and on. Surprisingly, the Army hadn’t considered that sourcing the raw materials would be an issue, and other bidders had not mentioned it.

Once the brass began realizing that this was a more complicated mission than they’d anticipated, the Yes Guy stepped in and laid out Sorinex’s grand strategy. He explained that they’d probably need slightly more than six months but that they’d been quietly reawakening old American factories to help them carry out new and innovative ways to make this, the largest order of fitness equipment ever, happen.

Then the meeting was over, and Lewis and Sorin were left with the rub: “We [were thinking we] might get the job, we might not,” Lewis recalls. “But if we do get the job and don’t invest in it ahead of time—like right now—we can’t fulfill it.”

If they did invest and didn’t get it? “Well, the house might burn down,” said Sorin. It was a huge gamble: They’d have sunk their capital into fulfilling an order that didn’t exist.

THE U.S. MILITARY first started thinking that measuring fitness might give our troops an edge in the mid-1800s. Our immigrant soldiers were using Turnverein training, a method based in calisthenics and gymnastics they’d brought over from Germany. The Army sent a lieutenant on a three-year fact-finding mission to Europe in 1859. Based on what he’d learned, he proposed a physical--education curriculum and standards for cadets and officers at West Point. It included climbing a 15-foot wall; vaulting a horse five feet high; running a mile in eight minutes or less; and doing a one-hour, three-mile march loaded with 20 pounds of gear. In other words, a pretty good functional-fitness test.

“Then, coming out of Vietnam, we were moving into a garrison environment,” says Whitfield B. East, Ph.D., Ed.D., who has been a professor of exercise science since the late 1970s and who, since 2000, has researched and developed fitness training for the Army. Many higher-ups in the military during the cold war believed that “nuclear weapons were so prolific that we would never fight another land battle, because war would ultimately result in some nuclear confrontation,” says East. “So people started thinking about [transitioning from combat-related fitness] to health-related fitness.” In 1980, the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) was instituted, which consisted of max pushups in two minutes, max situps in two minutes, and a two-mile run.

Two decades later, the planes hit the towers and troops were back on the ground, fighting a kinetic new form of warfare. While weighed down with anywhere from 90 to 130 pounds of gear and armor, infantrymen were sprinting short distances, covering long distances over uneven terrain, kicking in doors, climbing up ledges and walls, rapidly lifting and hauling heavy items, and more. “We were underprepared from a physical standpoint,” says East. The APFT was, in fact, only 40 percent predictive of a soldier’s ability to fight well in battle. Modern combat requires serious back, glute, and hamstring strength—muscle groups the test didn’t touch.

Soldiers were paying the price. Around half of active soldiers are injured every year, and 70 percent of those are overuse injuries, like tendon injuries and stress fractures. Our unfit soldiers were 49 percent more likely to be injured than fit ones were, and we were losing millions of workdays and spending billions of dollars treating injuries that likely could have been prevented with smarter fitness training.

By 2012, the military was conducting research to determine what sort of test would better prepare troops for combat. “We identified 113 common soldier tasks and distilled those down to 11 that were of high [physical] demand,” says East. “Then we deconstructed those and found that there were five key physical constructs within those 11 tasks.” Stuff like moving under load and over obstacles, engaging in hand-to-hand combat, moving heavy weights quickly, and so on. Then from there it was simply R&D to find the right series of exercises that simulated those constructs.

This new test would be used to assess each soldier’s fitness level, and the Army would provide them with an app that helped them train. This would, it thought, alleviate existing fitness problems, reduce injuries, and help better prepare incoming soldiers for combat. New recruits tended to be dangerously out of shape because of the larger demographic shift toward obesity ravaging the population. Only 29 percent of Americans ages 17 to 24 could qualify for service, and one of the most common causes for disqualification is obesity, which the CDC predicts will continue to increase over the next 15 years, further decreasing the Army’s pool of eligible candidates. One policy think tank deemed the military’s inability to find decent recruits a “looming national-security crisis.”

The new test was called the Army Combat Fitness Test (ACFT). Each ACFT kit would include a hex barbell, 18 bumper plates, and a pair of barbell collars for the deadlift; two 40-pound kettlebells for the carry; a sled for the drag; and a ten-pound medicine ball for the toss. “When the government needs to buy material, it issues what’s called an RFP, or request for proposal, and it basically says, ‘We have to buy X amount of Y material,’ ” says Will Allen, a cofounder of Harpoon Ventures, a venture-capital firm that specializes in defense contracting. “When an RFP drops, there is open and fair competition for businesses to pursue that contract.” The RFP for the ACFT equipment posted on December 28, 2018. The bidding began.

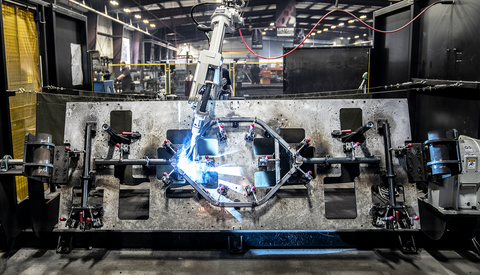

BEFORE YOU GET to the space-age-looking machines cutting barbells with a blue laser. Or the red-hot steel squat-rack beams hanging to cool. Or the fiery blast furnaces from which they come. Before you reach all that, you see that the walls flanking the entrance to the Sorinex factory floor are covered with steel logo plates custom-stamped with different insignias and coated in different colors. There are hundreds of them. These logo plates run atop every custom weight rack Sorinex makes for its clients. And it always makes an extra to proudly display on these walls.

There are plates from the weight rooms of the Denver Broncos, the Chicago Bears, the New England Patriots, the Los Angeles Lakers, the Dallas Mavericks, the Boston Red Sox, the New York Yankees, the Philadelphia Flyers, the UFC, and all the D-I powerhouse schools: Texas, Stanford, Georgia, Oregon, etc. There are also logo plates from notable home-gym orders: Joe Rogan’s gym, Hulk Hogan’s gym, Jocko Willink’s gym.

Bert Sorin’s father, Richard, was the guy you called when you had a special request. The lifting-obsessed PE teacher and self-taught welder started making gear in his carport in 1980. It was stuff designed for fastidious meatheads at the highest level of performance. People who needed their equipment just so. Word spread, and soon he was taking custom orders for others at the extremes of physical performance. Powerlifters, Olympic weightlifters, D-I football teams.

By 1987, he’d built the country’s largest custom weight room, for the University of Kentucky football team. In 1992, he took the gig from hobby to full-fledged company, which he called Sorinex. Every job is custom. The materials are American and the best.

Some of those plates hold the logos and acronyms of America’s most elite fighting forces, like the Navy SEALs and Air Force Special Operations Command. “We’re pretty tight with the military. We’ve kind of been the go-to guys for equipment for a lot of the special--forces units in all the different branches for many years,” says Sorin. “Maybe four or five years ago, we started hearing rumblings that they were going to be changing all their performance metrics within the Army, and it was going to change how everything has been done. So we started thinking about that.”

Exercise-equipment manufacturers don’t make every piece of gear in-house. Like a lot of companies in resource--intensive industries, such as electronics, cosmetics, and clothing, they’ll work with different suppliers and manufacturers to source different parts of their products, and in some cases, they may even work with third parties to customize and manufacture the whole product for them. For example, in 2019, the country had just two plants that manufactured crumb-rubber bumper plates. Equipment companies like Sorinex work with those manufacturers to develop bumper plates to their specifications.

Take the 1.5-inch tubular steel that Sorinex needed for its hex bars. Steel is milled into different shapes, like sheets and tubes of specific dimensions. Mills attempt to anticipate demand for steel products and produce accordingly, says Timothy Gill, chief economist for the American Iron and Steel Institute. But Sorinex was asking for “train-car-loads of steel,” as Lewis puts it, in a very specific shape, immediately—even though Sorinex had not yet won the contract. Expecting a steel crunch, Sorinex bought as much existing steel as possible from U. S. mills and made orders for as much as could be produced.

Second, there weren’t enough manufacturers to get the job done quickly enough. “So our whole approach was ‘To heck with the standard resources,’ ” says Lewis. “Instead of regurgitating the same [equipment and materials] sources out there, we introduced brand-new sources for the products. We’d found a spring-collar guy who would make spring collars in America. We found a new casting company who could make the kettlebells for us. We sourced the sleds from yet another manufacturer. And, of course, we could make the hex bars.”

To solve the bumper problem, Sorinex “worked with a company to introduce a new source for the rubber bumpers,” says Lewis. Then they figured out a way to give America a third bumper-plate manufacturer, making plans to lease a factory in Florida and “bring it up out of the ground to help deal with the order.”

For all those kettlebells, Sorin called an old company housed in a red-brick foundry in Bremen, Indiana, called BCI Solutions. “They were a small [family-owned] mom-and-pop-type organization who previously had a small history of making kettlebells,” he says. “We asked them, ‘What can you do?’ ”

“We manufacture for several industries, which include agriculture, construction, oil, and gas,” says Steve Pfefferle, director of sales for BCI. Think nuts and bolts, cast-iron parts, and automotive parts. “When we first spoke with Sorinex, it was a conversation [about] contracts, timelines, and project management.” The company got to work, creating molds for the kettlebells, which Sorinex signed off on.

One problem: BCI would have to ship a bunch of heavy iron balls—items that become cannonballs in the back of a freight truck rolling down the freeway at 75 miles per hour. “Each truckload was in the neighborhood of 40,000 pounds,” says Pfefferle. “[Sorinex and BCI] had to work together in developing packaging that would ensure safe delivery.”

Sorinex also talked to Mondo Polymer Technologies in Reno, Ohio, about producing the medicine balls. Each was to weigh ten pounds and be covered in grippy, non-squish liquid PVC. “The conversations were very frank,” recalls Joe Sikorski, the national sales manager at Mondo. Sorinex was clear about the scale and frantic nature of the job. Mondo even had its own meeting with the military. A vetting. “We believed we had the capacity, but if any [problems] happened, we had to supply the military before we were going to supply anyone else,” he says. “Then we [got ready to] put our nose to the grindstone.”

Which required doubling the number of molding machines that make the balls, from six to 12. “So that doubled our capacity there,” says Sikorski. Then they planned to shift their operating times. Standard eight-hour days would be history. This order would require running around the clock, 24 hours a day for five days a week.

Plans were laid. Materials stockpiled. New manufacturing partners rallied. It had been 13 months since the Army dropped its ACFT RFP, and after some creative planning, intense negotiating, and scary commitments made to manufacturers, Sorinex submitted its proposal along with ten other equipment companies by the deadline of February 4, 2019. The Army took four months to decide on the winner.

It split the contract between Sorinex and Atlantic Diving Supply, a major military contractor.

What likely made the Sorinex bid stand out, says Allen, the venture capitalist, was the company’s history supplying elite units with gear and its ability to anticipate problems the military didn’t think of and bring solutions. For example, it foresaw that the military was going to have a big storage problem if each kit was shipped on its own pallet. “Pops [Richard Sorin] came up with the idea to make sealable plastic cases for the kits,” says Sorin. “Each item fit exactly in its own place. The military could stack and store them. It was weatherproof, and it didn’t create any waste.” By innovating their way around using wooden pallets, Sorinex avoided the thousands of pounds of trash the pallets would’ve created.

“We were fishing for Moby Dick,” says Sorin. “But what happens when you get him on the line? There’s a quick moment of excitement. Then it’s ‘Oh, crap.’ ”

AS SORIN TOLD his employees and partners to get to work, word came down from the Army in July: Among the ten other companies that had submitted bids, two were protesting the contract, claiming they’d been unfairly overlooked. It wasn’t possible for Sorinex to make all those bumpers in the U. S., one firmly believed. A company that zigged couldn’t fathom the zag. The U. S. Government Accountability Office had to stop the project and investigate.

They all sat around for months, surrounded by steel.

By the time the Army and GAO lawyers denied both protests and gave the green light, it was October 2019.

Within a few months, Covid-19 would start to wreak havoc on the industry. “The pandemic scrambled supply chains as well as the logistics involved in getting those materials from point A to point B,” says Gill, the economist. And not just for steel, he points out—it was harder for manufacturers to get pretty much anything. Lewis’s early gamble on hoarding steel paid off, giving Sorinex just enough to keep manufacturing as it frantically searched for more.

The next problem was that they couldn’t build equipment from behind a computer screen. It takes hot, in-person factory labor. Sorinex had to apply for an essential-business designation to continue producing. To keep employees socially distanced, they worked in shifts around the clock. The upshot was that they could help alleviate one of the many burdens of the pandemic.

“We needed extra bodies,” says Sorin. “So we started pulling people from our community, hiring bartenders and workers from businesses that had closed down so they could make their bills. Shipping and boxing and labor jobs.”

One reality hadn’t changed: The Army was asking Sorinex to do a job in six months that would regularly take four years. Its manufacturing partners were moving too slowly, so Sorin and Lewis had to innovate around that.

“When you have to [make a piece of equipment] 18,000 times, if you can save ten seconds every time you make it, that saves a lot of time,” Lewis says. He worked with Sorinex’s partners, making tweaks to production flows that added up to big changes. “A company would say, ‘I can’t produce that many things a day,’ and [I’d say] ‘Okay, well, let’s move your raw materials 15 feet closer to where you’re making them into equipment.’ ”

Or take those cases that Sorinex made for each equipment kit. “That decision cut down on construction labor and resources for pallets,” says Sorin. “That alone saved over a million nails. The storage alone for the materials and all the sawdust from constructing pallets would have been overwhelming.”

DESPITE TAKING nine months rather than six, Sorinex had collected everything from all the American factories it had reinvigorated, filled the final ACFT equipment case, and shipped it to the military when I visited the company’s headquarters. Sorin and Lewis were in Sorin’s office, both sinking back into leather chairs, happy to reflect on the craziness of the process.

Their big early gambles—banking steel and staking their reputation with partners—had paid off. “It was a nightmare. It was a logistics nightmare. It was a storage nightmare. It was a purchasing nightmare,” says Lewis. “But I enjoyed the heck out of it. It was nice to see all that work done in America with American resources. To give a huge boost to our partner companies. We hired 50 or 60 people because of the project.”

American companies, all zagging together to produce:

1,098,240 pounds of hex barbells.

10,067,200 pounds of bumper plates.

183,040 pounds of medicine balls.

1,464,320 pounds of kettlebells.

The total value of the RFP bid: $64 million.

Sorinex started delivering the first of 18,304 ACFT kits to Army bases in late December 2019—starting with the Army National Guard in Frankfort, Kentucky. It finished delivering the order in July 2020. The Army officially began using the ACFT test that October.

Already military physical capability seems to be improving. “[The ACFT] challenges everyone. It’s aspirational,” says East. “If you [get] a perfect score, you really stand apart.” Just as Sorinex pursued—and achieved—the seemingly impossible with the ACFT order, so have nearly 1,000 soldiers, out of the more than 500,000 who have already taken the test, earned perfect scores.